The Pension Savings Tax Charge… could result in a Tax Saving?

Pension Savings Tax Charge

Each tax year, a UK resident individual who is a member of a registered pension scheme is entitled to an annual allowance in respect of pension contributions. For the 2023/24 tax year, the standard annual allowance is £60,000. The annual allowance effectively sets a limit on total contributions that can attract income tax relief. The total contributions made to an individual’s pension scheme for a tax year is referred to as their ‘pension input amount’ (“PIA”).

The annual allowance available may be increased by any unused annual allowance from the prior three tax years, subject to tapering for high earners both in the current and prior years, and the trigger of the money purchase annual allowance (“MPAA”). The details of annual allowance tapering and the MPAA are beyond the scope of this article, but for more information please refer to HMRC’s Pensions Tax Manual at PTM057000 and PTM056500.

If an individual’s PIA exceeds their available annual allowance for a tax year, they’ll be subject to what is known as a ‘pension savings tax charge’ (“PSTC”). The is an addition at Step 7 of the income tax computation outlined at ITA 2007, s 23.

The PSTC is computed by ‘pretending’, for the purposes of the calculation, that the excess contribution above the annual allowance (referred to as the ‘chargeable amount’ in the legislation) forms the ‘top-slice’ of a person’s taxable income. Technically, it is computed by taxing it as if it were added to the individual’s reduced net income per Step 3 of the Tax Computation at ITA 2007, s 23. This means it is always subject to the individual’s highest marginal rates of income tax, based on the parts of their relevant tax bands unused by their ordinary taxable income.

Usually, an individual would be advised to keep their pension contributions below their available annual allowance to ensure they do not trigger the PSTC, as it effectively negates any tax advantage that the person would obtain.

However, in some circumstances, tactically contributing more than the annual allowance and suffering a PSTC may result in an income tax saving! Broadly, this will occur when by making such an excess contribution the individual preserves a personal allowance that would otherwise have been abated.

Abatement of the Personal Allowance

To consider this in more detail, it is worth recapping that where an individual’s ‘adjusted net income’ (“ANI”) exceeds £100,000, their tax-free personal allowance for income tax is abated by £1 for every £2 the ANI exceeds the threshold. As standard, the personal allowance for the 2023/24 tax year is £12,570. Where an individual’s ANI is greater than or equal to £125,140, their personal allowance will be fully abated (i.e. reduced to nil).

This creates an effective tax rate in the income bracket from £100,000 to £125,140 of 60%; i.e. the individual effectively pays 60p of income tax for every £1 of gross income in this £25,140 bracket (please note, this assumes the income subject to tax is non-savings income).

Interaction

It is the interaction between these two mechanisms where the PSTC could, in fact, provide an overall tax saving. Consider the following illustration:

Illustration 1

Mr Jones earns a gross annual salary of £100,000 from his employment with Widgets plc. His employer makes an employer pension contribution to Mr Jones’ Self-Invested Personal Pension (“SIPP”), a defined contribution scheme, of £60,000 in 2023/24. Mr Jones doesn’t have any unused annual allowance from prior tax years, nor does he receive any other source of income.

The company has been very successful in the 2023 financial year, and on 31 March 2024, Mr Jones is awarded with a discretionary bonus of £20,000 to be paid shortly thereafter.

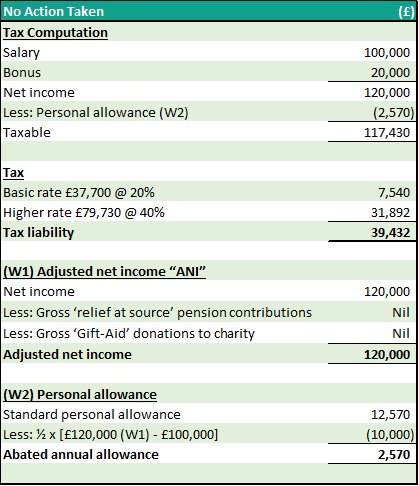

No action taken

Without taking further action, Mr Jones would face an effective income tax rate of 60% on the £20,000 bonus, as it would cause his tax-free personal allowance to be reduced by £10,000. Computing his tax position for 2023/24 without taking any further action, Mr Jones would have a tax liability of £39,432, calculated as follows:

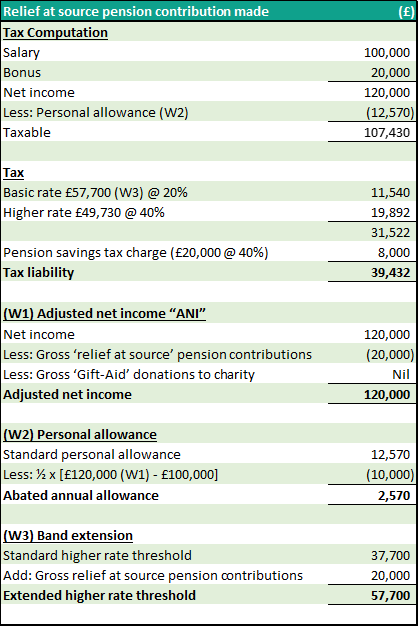

Relief at source pension contribution made

Instead, let’s consider the outcome if Mr Jones were to make a gross relief at source pension contribution of £20,000 to his SIPP on or before the 5 April 2024:

Prima facie, it appears Mr Jones gains no advantage as his tax liability remains the same both before and after the relief at source contribution; i.e. £39,432. However, to achieve the gross relief at source contribution of £20,000, he only needs to make a net contribution of £16,000; £4,000 of basic rate relief will be reclaimed from HMRC by the pension scheme administrator and added to Mr Jones’ SIPP. Crucially, the £4,000 that he didn’t need to contribute to his pension, he gets to keep, and hence overall he’s £4,000 better off.

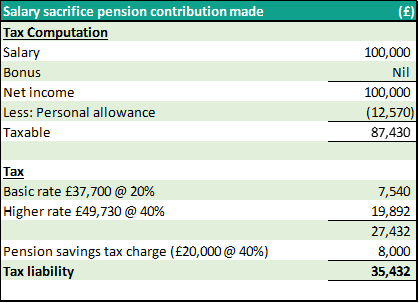

Salary sacrifice pension contribution made

Opting to salary sacrifice the bonus in favour of pension contributions, essentially relinquishing the bonus in lieu of a further employer pension contributions of £20,000, results in a tax liability of £35,432:

Due to the reduction in the overall tax liability, this once again, leaves Mr Jones £4,000 better off than simply doing nothing.

Summary

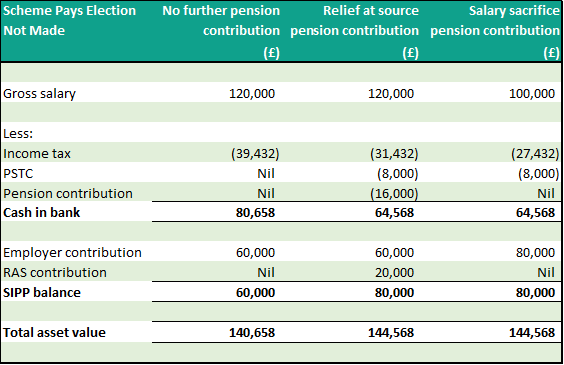

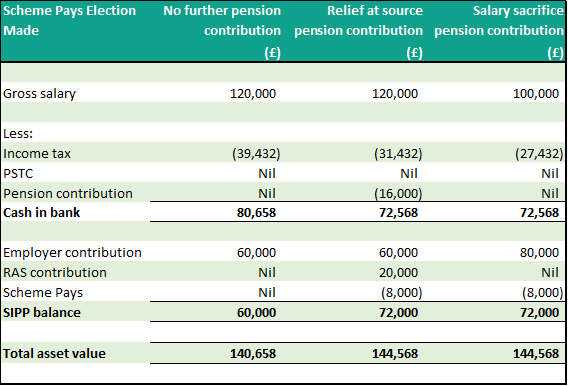

We can summarise the three scenarios as follows where a Scheme Pays election is not made (ignoring the effects of National Insurance Contributions):

Or alternatively if a valid Scheme Pays election is made by 31 July 2025 (again, ignoring the effects of National Insurance Contributions):

As you can see, despite suffering the PSTC in both scenarios where Mr Jones has used his discretionary bonus to make a pension contribution, his net asset value has still increased by £4,000 overall. This does of course, come at the cost of reducing his expendable cash by £16,000 or £8,000 respectively, but the short-term tax efficiency is still evident. Furthermore, this ignores the potential when opting to salary sacrifice the bonus, for both the employee and employer to benefit from Class 1 National Insurance (and possibly, for the employee, Student Loan Deduction) savings.

Admittedly, this is perhaps a rather academic scenario, as I imagine it would be quite rare to come across this in practice, but the point is that in the rush to get Self-Assessment tax returns completed by the 31 January filing deadline, advisers ought to take a moment to reflect on whether the general tax doctrine of “X is good” or “Y is bad” fits their client’s particular circumstances. As demonstrated above, the grimace that is usually worn by an adviser when discussing the PSTC with their client, may be softened with a smile where one sees the bigger picture.

Ryan Ward-Cabello

Tax Consultant

Related News Articles

Mileage Tax Relief Guide

Guide to Claiming Tax Relief on Mileage Expenses (Where Reimbursed Below HMRC Rates) Step 1: Confirm Eligibility You may claim tax relief if: - The mileage relates strictly to business travel (not ordinary commuting). - You are using your own vehicle. - Your employer reimburses you below the HMRC Approved Mileage Allowance Payments (AMAP): -…

Government to Raise Income Threshold for Self-Assessment Reporting and Launch Simple Online Tax Payment System

Move expected to reduce administrative burdens for up to 300,000 taxpayers The Government has announced its intention to raise the income threshold at which individuals are required to register for Self-Assessment. This change will affect taxpayers with low levels of trading, property, or miscellaneous income and forms part of a broader package aimed at simplifying…

Mandatory Real-Time Reporting of Benefits in Kind Delayed Until April 2027

HMRC delays mandatory payrolling of most employee benefits by one year HM Revenue & Customs (HMRC) has confirmed a 12-month delay in the implementation of mandatory real-time reporting for most benefits in kind (BiKs). Initially expected to come into force in April 2026, the requirement will now apply from April 2027. This extension follows feedback…